(Essay)

Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence

Adrienne Rich, 1989

Adrienne Rich was an American poet, essayist, and a non-fiction writer. The selected essay is one of the first to address the theme of lesbian existence. She discusses where misogyny and homophobia intersect and how the enforcement of heterosexuality within a patriarcal society is specific to the lesbian experience. Even though this essay opened up new discussions and understandings regarding the oppression of women and lesbians, she is also very much criticized for her participation in incredibly transphobic and especially transmisogynist discourses.

(Poetry)

Certain Magical Acts

Alice Notley, 2016

It is written about American poet Alice Notley that her ‘(...) early work laid both formal and theoretical groundwork for several generations of poets; she is considered a pioneering voice on topics like motherhood and domestic life.’ Describing her work in an interview she said: ‘I think I try with my poems to create a beginning space. I always seem to be erasing and starting over, rather than picking up where I left off, even if I wind up taking up the same themes. This is probably one reason that I change form and style so much, out of a desire to find a new beginning, which is always the true beginning.’

I went down there, played the drum, called to everyone.

I have found you because you’re there, all of you.

I want to hear what you say; I’ll speak what

you tell me to. I don’t think this is about love;

you are telling me we need a new description.

Maybe a new language, but you want to understand it. Everything I say from now on you are saying

to me. In many languages, from many faces; I’m your mouth.

I saw you

come to me

as if you were

a god; as if

a god were the essence of all us.

(Essay)

Uses of the Erotic: the Erotic as Power

Audre Lorde, 1980

‘Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,’ was one of many ways Audre Lorde described herself. Her activist work is very much linked to her writing, and in the essay, she is formulating the importance of discovering the erotic power within ourselves????; ‘We need each one of us,’ as she put it when presenting the text at a reading, ‘to deal from a place where we are most powerful. And what I wanted to talk about today was the erotic as a source of that power, and how urgent it is that we recognise that within ourselves.’

(Film)

Carol

2015

Carol is a film directed by Todd Haynes. The script was written by Phyllis Nagy, an American theatre and film director as well as a screenwriter and playwright. It is based on the romance novel The Price of Salt by Patricia Highsmith. Set in 1952 in New York City, it follows Therese Belivet, an aspiring photographer who meets Carol Aird, a glamorous older woman going through a difficult divorce.

(Short Story)

The Headstrong Historian

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 2008

The Headstrong Historian is a short story that looks at three generations of Nigerians, through which education, religion, family, and cultural heritage are explored. The author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is a Nigerian writer of novels, short stories, and non ction. She is also notably known for her acclaimed lectures ‘The Danger of a Single Story’ and ‘We should all be feminists’.

Many years after her husband had died, Nwamgba still closed her eyes from time to time to relive his nightly visits to her hut, and the mornings after, when she would walk to the stream humming a song, thinking of the smoky scent of him and the firmness of his weight, and feeling as if she were surrounded by light. Other memories of Obierika also remained clear—his stubby fingers curled around his flute when he played in the evenings, his delight when she set down his bowls of food, his sweaty back when he brought baskets filled with fresh clay for her pottery. From the moment she had first seen him, at a wrestling match, both of them staring and staring, both of them too young, her waist not yet wearing the menstruation cloth, she had believed with a quiet stubbornness that her chi and his chi had destined their marriage, and so when he and his relatives came to her father a few years later with pots of palm wine she told her mother that this was the man she would marry. Her mother was aghast. Did Nwamgba not know that Obierika was an only child, that his late father had been an only child whose wives had lost pregnancies and buried babies? Perhaps somebody in their family had committed the taboo of selling a girl into slavery and the earth god Ani was visiting misfortune on them. Nwamgba ignored her mother. She went into her father’s obi and told him she would run away from any other man’s house if she was not allowed to marry Obierika. Her father found her exhausting, this sharp-tongued, headstrong daughter who had once wrestled her brother to the ground. (Her father had had to warn those who saw this not to let anyone outside the compound know that a girl had thrown a boy.) He, too, was concerned about the infertility in Obierika’s family, but it was not a bad family: Obierika’s late father had taken the Ozo title; Obierika was already giving out his seed yams to sharecroppers. Nwamgba would not starve if she married him. Besides, it was better that he let his daughter go with the man she chose than to endure years of trouble in which she would keep returning home after confrontations with her in-laws; and so he gave his blessing, and she smiled and called him by his praise name.

To pay her bride price, Obierika came with two maternal cousins, Okafo and Okoye, who were like brothers to him. Nwamgba loathed them at first sight. She saw a grasping envy in their eyes that afternoon, as they drank palm wine in her father’s obi; and in the following years—years in which Obierika took titles and widened his compound and sold his yams to strangers from afar—she saw their envy blacken. But she tolerated them, because they mattered to Obierika, because he pretended not to notice that they didn’t work but came to him for yams and chickens, because he wanted to imagine that he had brothers. It was they who urged him, after her third miscarriage, to marry another wife. Obierika told them that he would give it some thought, but when they were alone in her hut at night he assured her that they would have a home full of children, and that he would not marry another wife until they were old, so that they would have somebody to care for them. She thought this strange of him, a prosperous man with only one wife, and she worried more than he did about their childlessness, about the songs that people sang, the melodious mean-spirited words: She has sold her womb. She has eaten his penis. He plays his flute and hands over his wealth to her.

Once, at a moonlight gathering, the square full of women telling stories and learning new dances, a group of girls saw Nwamgba and began to sing, their aggressive breasts pointing at her. She asked if they would mind singing a little louder, so that she could hear the words and then show them who was the greater of two tortoises. They stopped singing. She enjoyed their fear, the way they backed away from her, but it was then that she decided to find a wife for Obierika herself.

Nwamgba liked going to the Oyi stream, untying her wrapper from her waist and walking down the slope to the silvery rush of water that burst out from a rock. The waters of Oyi seemed fresher than those of the other stream, Ogalanya, or perhaps it was simply that Nwamgba felt comforted by the shrine of the Oyi goddess, tucked away in a corner; as a child she had learned that Oyi was the protector of women, the reason it was taboo to sell women into slavery. Nwamgba’s closest friend, Ayaju, was already at the stream, and as Nwamgba helped Ayaju raise her pot to her head she asked her who might be a good second wife for Obierika.

She and Ayaju had grown up together and had married men from the same clan. The difference between them, though, was that Ayaju was of slave descent. Ayaju did not care for her husband, Okenwa, who she said resembled and smelled like a rat, but her marriage prospects had been limited; no man from a freeborn family would have come for her hand. Ayaju was a trader, and her rangy, quick-moving body spoke of her many journeys; she had even travelled beyond Onicha. It was she who had first brought back tales of the strange customs of the Igala and Edo traders, she who had first told stories of the white-skinned men who had arrived in Onicha with mirrors and fabrics and the biggest guns the people of those parts had ever seen. This cosmopolitanism earned her respect, and she was the only person of slave descent who talked loudly at the Women’s Council, the only person who had answers for everything. She promptly suggested, for Obierika’s second wife, a young girl from the Okonkwo family, who had beautiful wide hips and who was respectful, nothing like the other young girls of today, with their heads full of nonsense.

As they walked home from the stream, Ayaju said that perhaps Nwamgba should do what other women in her situation did—take a lover and get pregnant in order to continue Obierika’s lineage. Nwamgba’s retort was sharp, because she did not like Ayaju’s tone, which suggested that Obierika was impotent, and, as if in response to her thoughts, she felt a furious stabbing sensation in her back and knew that she was pregnant again, but she said nothing, because she knew, too, that she would lose it again.

Her miscarriage happened a few weeks later, lumpy blood running down her legs. Obierika comforted her and suggested that they go to the famous oracle, Kisa, as soon as she was well enough for the half day’s journey. After the dibia had consulted the oracle, Nwamgba cringed at the thought of sacrificing a whole cow; Obierika certainly had greedy ancestors. But they performed the ritual cleansings and the sacrifices as required, and when she suggested that he go and see the Okonkwo family about their daughter he delayed and delayed until another sharp pain spliced her back, and, months later, she was lying on a pile of freshly washed banana leaves behind her hut, straining and pushing until the baby slipped out.

(Essay)

The Octopus in Love

Chus Martínez, 2014

Chus Martínez is a writer and curator, when introducing her essay, from which this piece is taken, she writes: ‘The octopus is the only animal that has a portion of its brain (three quarters, to be exact) located in its (eight) arms. Without a central nervous system, every arm “thinks” as well as “senses” the surrounding world with total autonomy, and yet, each arm is part of the animal. For us, art is what allows us to imagine this form of decentralized perception. It enables us to sense the world in ways beyond language. Art is the octopus in love. It transforms our way of conceiving the social as well as its institutions, and also transforms the hope we all have for the possibility of perceptive inventiveness.’

(Essay)

The Feminist Writers’ Guild

Dodie Bellamy, 2015

In the selected essay, Dodie Bellamy, writer and journalist, is describing her time as part of The Feminist Writers’ Guild in the U.S. during the eighties. It deals with the importance of meeting and having conversations in the physical presence of one another, and the idea that political change starts in the emergence of issues and actions of the small collective.

In her book Intimate Revolt, Julia Kristeva argues that the “new world order,” which Guy Debord characterizes as “the society of the spectacle,” is not conducive to revolt. “Against whom can we revolt,” she asks, “if power is vacant and values corrupt?” In order to nurture a healthy questioning of the status quo, she proposes “tiny revolts.” “[W]e have reached the point of no return, from which we will have to re-turn to the little things, tiny revolts, in order to preserve the life of the mind and of the species.” Addressing the feminist movement, Kristeva suggests that “after all the more or less reasonable and promising projects and slogans,” feminism’s great contribution has been a “revalorizing of the sensory experience.” Of course we could argue with this, we could say “how patronizing,” we could shake our angers at Kristeva’s lengthy analyses of Barthes, Sartre, Aragon, and ask, why doesn’t she add at least one woman to the mix. We could mutter about her stilted, abstract style-like how sensual is that? But in her own way, Kristeva approves of feminism here. She lauds the sensory intimacy that arises out of “the universe of women” for it o ers “an alternative to the robotizing and spectacular society that is damaging the culture of revolt.”

(Letter)

Letter to Elizabeth Holland

Emily Dickinson, 1871

Emily Dickinson was an American poet born in 1830, after her death, nearly two thousand poems were discovered in her dresser drawer, only seven of them were published during her lifetime. She is famous for her extraordinary poetry, and as the chosen letter manifests, she could turn even the most commonplace happening into just that. Her friend Elizabeth had visited her and forgot the thimble of the sewing she had brought. In the letter, Emily responds with motive to tell her that she had found it, but perhaps even more to convey her appreciation of their friendship.

I have a fear I did not thank you for the thoughtful Candy.

Could you conscientiously dispel it by saying that I did?

Generous little Sister!

I will protect the Thimble till it reaches Home –

Even the Thimble has it’s Nest!

The Parting I tried to smuggle resulted in quite a Mob last!

The Fence is the only Sanctuary. That no one invades because no

one suspects it.

Why the thief ingredient accompanies all Sweetness Darwin

does not tell us.

Each expiring Secret leaves an Heir, distracting still.

Our unfinished interview like the Cloth of Dreams, cheapens

other fabrics.

That Possession fairest lies that is least possess.

Transport’s mighty price is no more than he is worth –

Would we sell him for it? That is all his Test.

Dont affront the Eyes –

Little Despots govern worst.

Vinnie leaves me Monday – Spare me your remembrance while

I buffet Life and Time without –

Emily.

(Book chapter)

La consciencia de la mestiza

Gloria Anzaldúa, 1987

‘La conciencia de la mestiza’ is the last chapter of Borderlands | La frontera, a semi-autobiographic book of essays, prose, and poems. It examines the issues of women’s experiences in Chicano and Latinx cultures. Anzaldúa was an American feminist and LGBT studies writer; in her texts, she discussed topics such as heteronormativity, colonialism, and male dominance. The borderlands is referring to the invisible borders existing between groups—dualities such as men and women, latinx and non-latinx, and differences in sexualities. The new mestiza is an image of the consciousness that wants to break these borders.

These numerous possibilities leave la mestiza floundering in uncharted seas. In perceiving con icting information and points of view, she is subjected to a swamping of her psychological borders. She has discovered that she can’t hold concepts or ideas in rigid boundaries. The borders and walls that are sup- posed to keep the undesirable ideas out are entrenched habits and patterns of behaviour; these habits and patterns are the enemy within. Rigidity means death. Only by remaining exible is she able to stretch the psyche horizontally and vertically. La mestiza constantly has to shift out of habitual formations; from convergent thinking, analytical reasoning that tends to use rationality to move toward a single goal (a Western mode), to divergent thinking, characterized by movement away from set patterns and goals and toward a more whole perspective, one that includes rather than excludes.

The new mestiza copes by developing a tolerance for contradictions, a tolerance for ambiguity. She learns to be an Indian in Mexican culture, to be Mexican from an Anglo point of view. She learns to juggle cultures. She has a plural personality, she operates in a pluralistic mode–nothing is thrust out, the good the bad and the ugly, nothing rejected, nothing abandoned. Not only does she sustain contradictions, she turns the ambivalence into something else.

She can be jarred out of ambivalence by an intense, and often painful, emotional event which inverts or resolves the ambivalence. I’m not sure exactly how. The work takes place underground–subconsciously. It is work that the soul performs. at focal point or fulcrum, that juncture where the mestiza stands, is where phenomena tend to collide. It is where the possibility of uniting all that is separate occurs. This assembly is not one where severed or separated pieces merely come together. Nor is it a balancing of opposing powers. In attempting to work out a synthesis, the self has added a third element which is greater than the sum of its severed parts. at third element is a new consciousness–a mestiza consciousness–and though it is a source of intense pain, its energy comes from continual creative motion that keeps breaking down the unitary aspect of each new paradigm.

En unas pocas centurias, the future will belong to the mestiza. Because the future depends on the breaking down of para- digms, it depends on the straddling of two or more cultures. By creating a new mythos–that is, a change in the way we perceive reality, the way we see ourselves, and the ways we behave–la mestiza creates a new consciousness.

The work of mestiza consciousness is to break down the subject-object duality that keeps her a prisoner and to show in the flesh and through the images in her work how duality is transcended. The answer to the problem between the white race and the colored, between males and females, lies in healing the split that originates in the very foundation of our lives, our culture, our languages, our thoughts. A massive uprooting of dualistic thinking in the individual and collective consciousness is the beginning od a long struggle, but one that could, in our best hopes, bring us to the end of rape, of violence, of war.

Su cuerpo es una bocacalle. La mestiza has gone from being the sacri cial goat to becoming the o ciating priestess at the crossroads.

Su cuerpo es una bocacalle. La mestiza has gone from being the sacri cial goat to becoming the o ciating priestess at the crossroads.

As a mestiza I have no country, my homeland cast me out; yet all countries are mine because I am every woman’s sister or potential lover. (As a lesbian I have no race, my own people disclaim me; but I am all races because there is the queer of me in all races.) I am cultureless because, as a feminist, I challenge the collective cultural/religous male-driven beliefs of Indo-His- panics and Anglos; yet I am cultured because I am participating in the creation of yet another culture, a new story to explain the world and our participation in it, a new value system with images and symbols that connect us to each other and to the planet. Soy un amasamiento, I am an act of kneading, of uniting and joining that not only has produced both a creature of darkness and a creature of light, but also a creature that questions the de nitions of light and dark and gives them new meanings.

We are the people who leap in the dark, we are the people on the knees of the gods. In our very flesh, (r)evolution works out the clash of cultures. It makes us crazy constantly, but if the center holds, we’ve made some kind of evolutionary step forward. Nuestra alma el trabajo, the opus, the great alchemical work; spiritual mestizaje, a “morphogenesis,” an inevitable unfolding. We have become the quickening serpent movement.

(Essay)

Laugh of the Medusa

Hélène Cixous, 1972

Hélène Cixous is a professor, writer, feminist, and founder of The University of Paris VIII. Her essay was first published in 1972 as ‘Le rire de la Méduse’ and made her well-known for her concepts of écriture feminine, described as a feminine mode of writing outside the patriarchal structures of language.

(Novel)

Two Serious Ladies

Jane Bowles, 1943

Two Serious Ladies is Jane Bowles’s only novel. She is known for her very singular way of writing, but also for her long-standing writers block; her body of work comprises one novel, one full-length play, a few shorter works, and a great number of letters. The novel follows two women who both feel the need to escape their suffocating social environment and decide, each in their own way, to radically change their ways of living.

At this moment Mrs Copperfield was strongly reminded of a dream that had recurred often during her life. She was being chased up a short hill by a dog. At the top of the hill there stood a few pine trees and a mannequin about eight feet high. She approached the mannequin and discovered her to be fashioned out of flesh, but without life. Her dress was of a black velvet, and tapered to a very narrow width at the hem. Mrs Copperfield wrapped one of the mannequin’s arms tightly around her own waist. She was startled by the thickness of the arm and very pleased. The mannequin’s other arm she bent upward from the elbow with her free hand. Then the mannequin began to sway backwards and forwards. Mrs Copperfield clung all the more tightly to the mannequin and together they fell off the top of the hill and continued rolling for quite a distance until they landed on a little walk, where they remained locked in each other’s arms. Mrs Copperfield loved this part of the dream best; and the fact that all the way down the hill the mannequin acted as a buffer between herself and the broken bottles and little stones over which they fell gave her particular satisfaction.

“Now,” said Pacifica, “if you don’t mind I will take one more swim by myself.” But first she helped Mrs Copperfield to her feet and led her back to the beach, where Mrs Copperfield collapsed on the sand and hung her head like a wilted flower. She was trembling and exhausted as one is after a love experience. She looked up at Pacifica, who noticed that her eyes were more luminous and softer than she had ever seen them before.

“You should go in the water more,” said Pacifica; “you stay in the house too much.”

She ran back into the water and swam back and forth many times. The sea was now blue and much rougher than it had been earlier. Once during the course of her swimming Pacifica rested on a large flat rock which the outgoing tide had uncovered. She was directly in the line of the hazy sun’s pale rays. Mrs Copperfield had a difficult time being able to see her at all and soon she fell asleep.

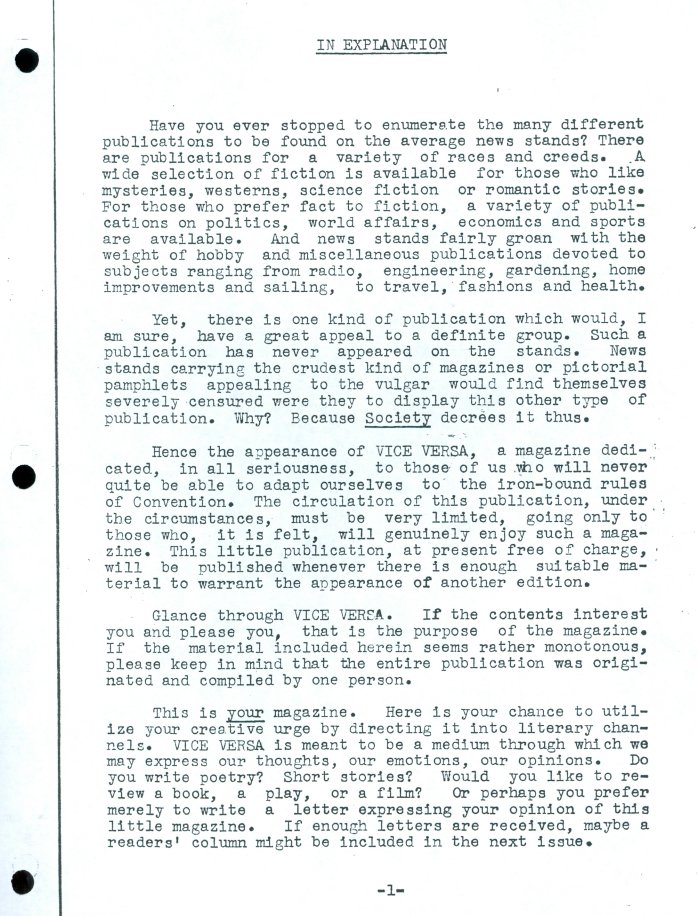

(Periodical)

Vice Versa, America's Gayest Magazine

Lisa Ben, 1947

Vice Versa is the first known lesbian publication in the world. Lisa Ben, an American editor, author, and songwriter, wrote, edited, printed, and distributed the magazine for nine months in Los Angeles in the late 1940s. She produced it at her work place after her boss told her that she should always look busy, even when she had no work assigned.

(Book)

Sexual Difference

Milan Women's Bookstore Collective, 1990

The selected quote was read on the screening of Our Future Network by artist and contemporary film maker Alex Martinis-Roe last year. The film deals with practices from different feminist groups. One practice called affidamento came from the Milan Women’s Bookstore Collective, it is a form of consciouness-raising based on a correspondence between two women. Roe writes ‘By referring to one another, each gives the other authority in her spheres of political practice by acknowledging her desires, competences and differences.’ (From her online archive alexmartinisroe.com)

Virginia Woolf maintained that in order to do intellectual work, one needs a room of one’s own. However, it may be impossible to keep still and apply oneself to work in that room because the texts and their subjects seem like extraneous, erosive blocks of words and facts through which the mind cannot make its way, paralysed as it is by emotions which have no corresponding terms in language. e room of one’s own must be understood differently, then, as a symbolic placement, a space-time furnished with female gendered references, where one goes for meaningful preparation before work, and confirmation after.

(Novel)

The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World

Margaret Cavendish, 1666

‘The Blazing-World’ is a work of prose fiction by the English writer Margaret Cavendish. It is the only known work of utopian fiction by a woman in the 17th century, and one of the earliest examples of science fiction. It explores issues such as science, gender and power, as well as the relationship between imagination and reason, philosophy and fiction.

(Poetry)

Poems

Sappho, 600 BC

Sappho came from the island of Lesbos in Greece and wrote a large body of poetry, much of which reflected love between women. Most of her work is lost; the chosen fragments come from Guy Davenport’s translations of what is left from 2600 years ago. In the introduction to the translations, Davenport writes: ‘Spirit, for Sappho, shines from matter; one embraces the two together, inseparable. The world is to be loved.’

(Video)

Tamera’s Heartfelt Birthday Message to Adrienne

Tamera Mowry-Housley and Adrienne Bailon, 2016

Tamera and Adrienne host alongside each other an American TV show called The Real. For Adrienne’s birthday, Tamera begins a spontaneous declaration of love for her coworker and friend by drawing in a long breath. She then slowly puts into words what she loves and admires her for by giving space to the un ltered expres- sion of her affection.

(Speech)

Meryl Streep’s Lifetime Achievement Award

Viola Davis, 2017

Viola Davis is an American actress and producer. She’s known for her many successful roles—but also for her often powerful and moving speeches. In her speech at the Emmys awards, she starts by quoting Harriet Tubman: ‘In my mind, I see a line. And over that line, I see green fields and lovely flowers and beautiful white women with their arms stretched out to me over that line, but I can’t seem to get there no-how. I can’t seem to get over that line.’ and she continues: ‘That was Harriet Tubman in the 1800s. And let me tell you something: The only thing that sepa- rates women of color from anyone else is opportunity.’

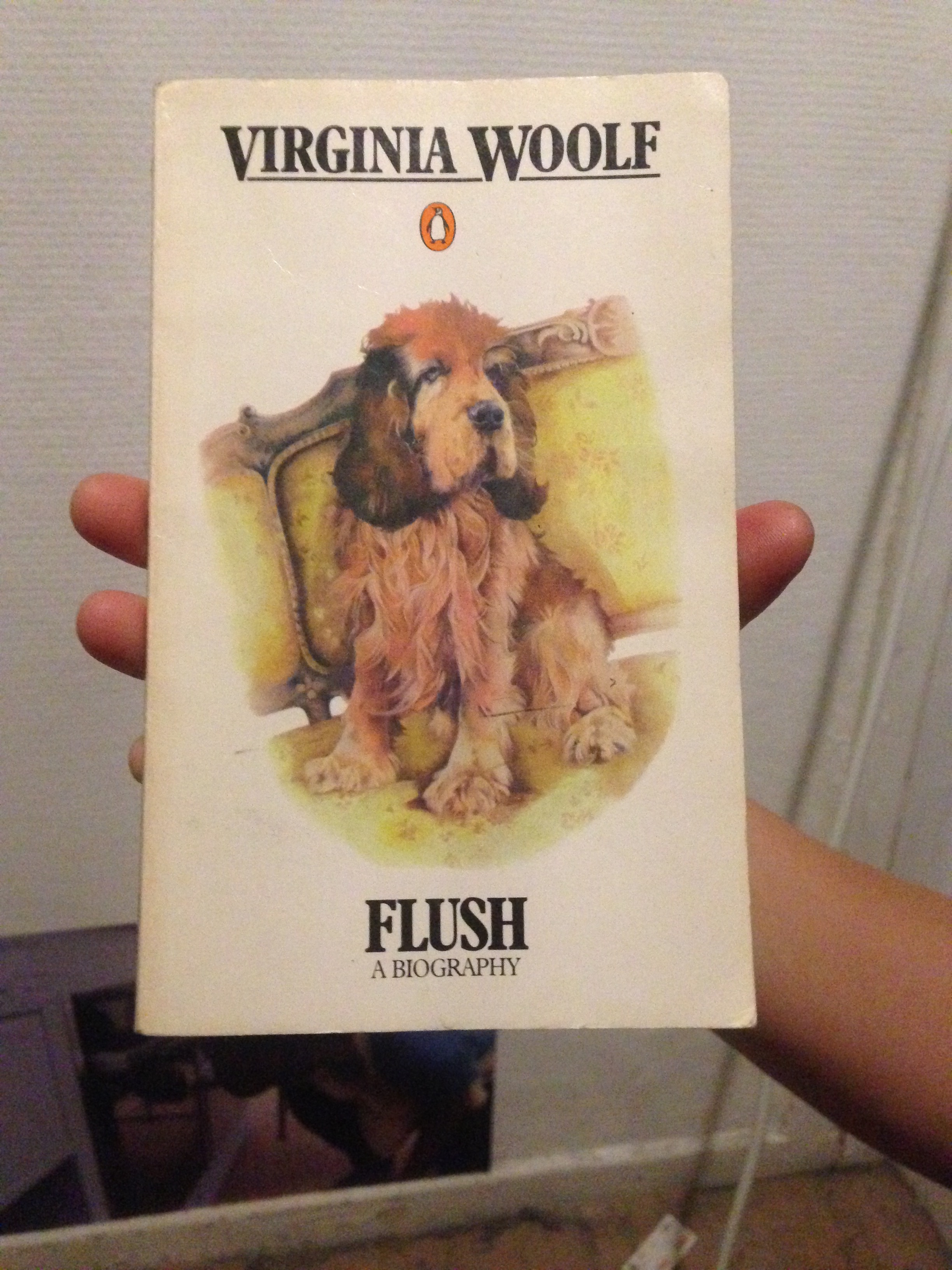

(Novel)

Flush

Virginia Woolf, 1933

Flush is an imaginative biography of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s dog, a cocker spaniel. It sways between fiction and non-fiction, and is based on Barrett Browning’s two poems about her dog as well as her correspondence with her husband. Virginia Woolf writes from the perspective of Flush and uses it as an opportunity to write about class differences, women’s freedom and the anxiety of city life.

And next day, as the fine weather continued, Miss Barrett ventured upon an even more daring exploit – she had herself drawn up Wimpole Street in a bath-chair. Again Flush went with her. For the first time he heard his nails click upon the hard paving-stones of London. For the first time the whole battery of a London street on a hot summer’s day assaulted his nostrils. He smelt the swooning smells that lie in the gutters; the bitter smells that corrode iron railings; the fuming, heady smells that rise from basements – smells more complex, corrupt, violently contrasted and compounded than any he had smelt in the fields near Reading; smells that lay far beyond the range of the human nose; so that while the chair went on, he stopped, amazed; smelling, savouring, until a jerk at his collar dragged him on. And also, as he trotted up Wimpole Street behind Miss Barrett’s chair he was dazed by the passage of human bodies. Petticoats swished at his head; trousers brushed his flanks; sometimes a wheel whizzed an inch from his nose; the wind of destruction roared in his ears and fanned the feathers of his paws as a van passed. Then he plunged in terror. Mercifully the chain tugged at his collar; Miss Barrett held him tight, or he would have rushed to destruction.